By the time you will read this, I will pass a very significant milestone. Well, two.

One is my 65th birthday – which I am proud to admit to.

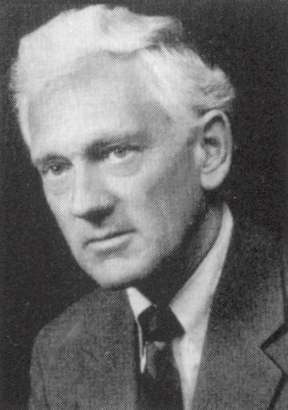

The second is outliving my father, who died just short of his 65th birthday: thirty-eight years ago. His name was James Stephenson, and during the course of his life he had several brushes with death. He was born on March 29, 1919, the year of the dreaded Spanish influenza, which nearly killed him at age six months.

Two decades later, he was in a US bomber flying over Germany when the aircraft was shot down. Out he leapt. And unlike the other members of the crew, he waited very long to open his parachute. He was the only one to survive. The only injury he sustained was a deep cut on his right ring finger made by a sharp tree branch as he crashed through the forest canopy. he almost made it to Allied territory when a young German boy turned him in. He spent two years in Stalag 1.

His parents were told he had died. And when my father was finally freed from the Prisoner of War camp and made it back to the United States, he found out that his parents had given away all his possessions and, in a way, he had to start his life all over again.

My father refused to speak a single word about any of this to me or my sister. By the time I arrived ten years later, both of his parents were already dead. His mother went first with uterine cancer. His father soon followed with a heart attack.

What eventually felled my father four and a half decades later was cancer of a different type – the dreaded pancreatic cancer. And here the story becomes rather strange, but I swear to its veracity.

In that year – 1985 – I was living in Santiago, Chile funded with a grant to do doctoral research. Shortly after I arrived, I met the man who would become my first husband: Ricardo. Some months later, when we were pretty sure we were going to get married, he took a job down in the southern portion of Chile to earn some money and I stayed with his family in Santiago. That was when we learned that his uncle (his father’s brother) had pancreatic cancer. And I watched the poor man Rene waste away in pain over the course of several months, with no one telling him that he was terminal, or even what malady he had.

Not long after Rene’s funeral, I had the most beautiful dream. One I will never forget. I saw my father in front of me as clear as day, and he was surrounded by a luminous light. Where his throat would be, there was instead a hole from which streamed this golden light. He was smiling and my heart melted with love. And he said to me very clearly: “Don’t be sad. The pain is all gone.”

The next morning, I received a phone call that he had died. Neither my sister nor I had even been informed he was sick.

We eventually learned that he had been hospitalized a week earlier with the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. He was a medical doctor by training and a Homeopath by practice, and when he learned of the prognosis, he refused all treatment the hospital staff offered. They claimed he was crazy and wished to impose an operation on him. He somehow managed to get a hold of a certain homeopathic remedy, swallowed the vial that tasted like sugar, and peacefully closed his eyes forever more.

When I met my second husband Terry long after my father had passed, I found out that his father had died even younger. His father had been fifty-one when he suffered a massive heart attack at Kingsbury’s Engine Lathe Department 26 in Keene. Terry was approaching that age when we first met, and would sometimes say to me: “Maybe I’ll meet the same fate as my father. Maybe I’ll have a heart attack soon.”

Luckily, this did not happen.

It can be strange yet powerful kind of milestone when we find ourselves older than our own parents ever were. And when we do, our life takes on a different tinge or slant. Almost like a gift. Or an encore. Or a chance to figure out something we still have left to do, and maybe, complete – something our parents could not, when they left this world so early and quite unexpectedly.

Leave a reply to Terry Clark Cancel reply